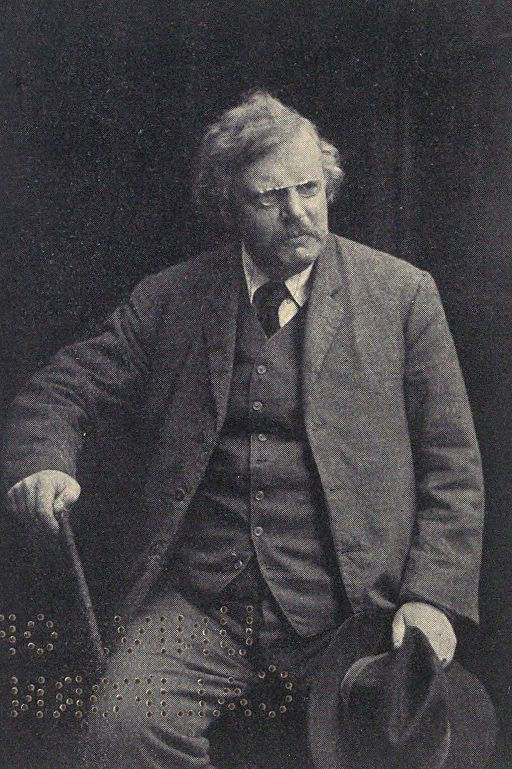

G.K. Chesterton From 1913 to 1920

- Brent Hecht

- Dec 8, 2023

- 8 min read

Gilbert Keith Chesterton was a prolific writer and Catholic Christian apologist. He wrote numerous books and collections of essays during his lifetime and first started writing poetry in 1886 as a 12-year-old.1 One author and story that Chesterton drew inspiration from was The Dragon and the Raven: The Days of King Alfred published in 1886 by famous British Author George Alfred Henty.2

Chesterton's first book was in 1900 called Greybeards at Play: Literature and Art For Old Gentleman which was a self-described book of rhymes and sketches. The next year, in 1901, Chesterton married Frances Blogg. Chesterton and his wife were unable to have children during their marriage. Chesterton became most well-known for his mysteries that involved a character, known as Father Brown. The Father Brown mystery series was made up of 53 stories in the collection. He wrote the first one in 1910 and completed the last one in the series in 1936.

In 1916, GK Chesterton became the head editor of a popular British publication called the New Witness. He replaced his brother, Cecil Chesterton, who was chosen to fight in World War I that year. Cecil Chesterton was killed in battle in 1918 and had previously worked as the managing editor of New Witness from 1912 to 1916 and was famous for exposing the Marconi Scandal. GK's comments related to the scandal are provided below. Prior to replacing his brother, GK was involved in his own political battles, such as his outspokenness against the British Mental Deficiency Act.

Chesterton and The British Mental Deficiency Act

In 1913, an act known as the Mental Deficiency Act was proposed and passed. GK Chesterton spoke out against the act. To understand why there was an act known as the Mental Deficiency Act, one should transport themselves back in time and understand the spirit of the age. At this time, eugenics was not only a popularly debated topic but also becoming popular in practice.

What is eugenics exactly? Chesterton provides a long and nuanced definition in his 1922 book, Eugenics and other Evils. He acknowledges that eugenics means different things to different peoples and so Chesterton defines it very broadly to avoid providing wiggle room for its evils and those who would promote it. Here are provided only a couple excerpts from his book.

I know that it means very different things to different peoples; but that is because evil always takes advantage of ambiguity. I know it is praised with high professions of idealism and benevolence; with silver-tongued rhetoric about purer motherhood and a happier posterity. But that is only because evil is always flattered as the Furies were called "The Gracious Ones." . . .evil always wins through the strength of its splendid dupes; and there has in all ages been a disastrous alliance between abnormal innocence and abnormal sin. . .3

When Chesterton refers to Furies, he is referring to characters from Greek Mythology which might be recognized synonymously in the Christian realm as deceptive, demonic forces. The next quote provides a more direct definition from the same book.

The shortest general definition of Eugenics on its practical side is that it does, in a more or less degree, propose to control some families at least as if they were families of pagan slaves.4

Very well-known people from Chesterton's time period were proponents of practicing eugenics. For example, Margaret Sanger, the mother of Planned Parenthood was an outspoken eugenicist. This is one reason she so adamantly advocated for women to prevent pregnancies via birth-control so that women could become "gods" and supposedly control their destinies. And it was Sanger who later paved the way towards legalized abortion. Woodrow Wilson was also a known supporter of eugenics. Today, the evil ideology of eugenics and all that it entails is losing the debate in the public square and Lord willing, it will continue to suffer defeat.

Strangely, the Mental Deficiency Act of 1913 was preceded by an act in 1886 known as The Idiots Act of 1886. The Mental Deficiency Act repealed The Idiots Act and it is clear and apparent that these two acts would not be considered politically correct in this day and age, and yet, these are two of the laws which paved the way towards the industrial scale mental health industry that is now present in Britain, America, and other nations. This article will not provide great details on what these laws set out to accomplish except this quote below. A separate article describing these laws in detail is written here.

It proposed an institutional separation so that mental defectives should be taken out of Poor Law institutions and prisons into newly established colonies.5

Poor Law institutions, referenced in the quote above, were simply places that housed the less fortunate in British society.

Chesterton's Comments on The Marconi Scandal

In 1912, the Marconi Scandal made headlines. The scandal originates from the fact that the Prime Minister H.H. Asquith had been tasked with creating a nationwide radio network. At this time, the British Empire was a vast and global empire and so creating a radio communications network for the British Empire was an enormous task. After considering different companies, the British government chose the British Marconi Company to accomplish the task. Shortly thereafter, allegations of insider trading in the shares of The Marconi Company surfaced, first being alleged from Cecil Chesterton at The New Witness.

GK Chesterton saw the Marconi Scandal as a watershed moment in history. In his autobiography, he described the importance of this event on the world. Given that he was Cecil's brother, he may have been partial and desired to honor his brother, yet he genuinely believed it was a moment where two paths were set before British citizens. One led to socialism and the other would lead to capitalism.

It is the fashion to divide recent history into Pre-war and Post-war conditions. I believe it is almost as essential to divide them into Pre-Marconi and Post-Marconi days. It was during the agitations upon that affair that the ordinary English citizen lost his invincible ignorance; or, in ordinary language, his innocence. And as I happened to play a part, secondary indeed, but definite, in the quarrel about this affair, and as in any case anything that my brother did was of considerable importance to me and my affairs. . . . I think it probable that centuries will pass before it is seen clearly and in its right perspective; and that then it will be seen as one of the turning-points in the whole history of England and the world.6

Here, Chesterton explicitly states that the unveiling of the Marconi Scandal rescued Brits and possibly the world from socialist principles. As is often the case with younger generations, he acknowledges that he and his kind were enamored with socialism in their youth.

If he wants to know what the Marconi Scandal has saved us from, I can tell him. It has saved us from socialism. My God! what socialism and run by what kind of socialists! My God! What and escape! If we had transferred the simplest national systems to the State (as we wanted to in our youth) it is to these men that we should have transferred them.7

An article providing more details on the Marconi Scandal can be found here.

Chesterton on World War I

Chesterton held strong views on World War I and the German nation. In 1914, he wrote an essay titled the Barbarism of Berlin where he describes the causes of World War I from his point of view. Granted, Chesterton was approaching the situation from a British point of view and he very clearly expressed his disgust towards Germany for starting the war. To Chesterton, cutting through any nuance of the causes was as simple as understanding that Germany wished to invade France and the easiest path to do so was to go through Belgium.

. . . it is as easy to answer the question of why England came to be in it at all, as it is to ask how a man fell down a coal-hole. . .Prussia, France, and England had all promised not to invade Belgium. Prussia proposed to invade Belgium, because it was the safest way of invading France.8

Here, once again Chesterton lays the blame for the war at the feet of Germany and more specifically, the Prussians.

Anyone can see this well enough, merely by reading the last negotiations between London and Berlin. The Prussians had made a new discovery in international politics: that it may often be convenient to make a promise; and yet curiously inconvenient to keep it.9

Chesterton also defined what he means by the name barbarian. He claimed that Germans would accuse their adversary of not playing by the rules of war, while they themselves would violate the rules. He provided an example where the German appealed to the Hague Conference of 1899 where dum-dum bullets were made illegal. Dum-dum bullets were bullets that would explode on impact and fracture within its victim, making it unlikely for the wounded to recover. Chesterton found it ironic that Germany violated an agreement that they would not invade Belgium, yet appealed to the Hague Conference as they accused France of its violation.

Do what he(German barbarian) will, he cannot get outside the idea that he, because he is he and not you, is free to break the law; and also to appeal to the law. It is said that the Prussian officers play at a game called Kriegsspiel, or the War Game. But in truth, they could not play at any game; for the essence of every game is that the rules are the same on both sides.10

Chesterton goes on to belabor the point that the Prussian German was a different kind of person. He states that the Prussian will have one-sided duels where one man is unfairly advantaged, making the duel uneven to begin with. It was these principles which caused Chesterton to call his adversary barbarians.

The fundamental fact, however, is the absence of the reciprocal idea. The Prussian is not sufficiently civilised for the duel. Even when he crosses swords with us his thoughts are not as our thoughts; when we both glorify war, we are glorifying different things. Our medals are wrought like his, but they do not mean the same thing; our regiments are cheered as his are, but the thought in the heart is not the same;11

In Chesterton's final paragraphs of the book, he states this regarding Germany's view of Britain, while subtly indicting Britain at the same time.

She thought that because our politics have become largely financial that they had become wholly financial; that because our aristocrats had become pretty cynical that they had become entirely corrupt. They could not seize the subtlety by which a rather used-up English gentleman might sell a coronet when he would not sell a fortress; might lower the public standards and yet refuse to lower the flag. In short, the Germans are quite sure that they understand us entirely, because they do not understand us at all.12

Other Writings

Chesterton had other well-known writings during the period from 1913 to 1920.

The Uses of Diversity(1917)

The Uses of Diversity Chesterton published in 1917 and was simply a collection of articles and essays from his time writing for the New Witness and the Illustrated London News.

New Jerusalem(1920)

In 1920, Chesterton published New Jerusalem which was a compilation of random thoughts. Dale Alquist calls it a "philosophical travelogue" of Chesterton's travels throughout Europe as well as to what was Palestine at the time.

The Superstition of Divorce(1920)

Chesterton published The Superstition of Divorce in 1920 and again attacks the heart of one of the rising moral issues of that time. Here is an excerpt from the book.

They must surely see that in England at present, as in many parts of America in the past, the new liberty is being taken in the spirit of license as if the exception were to be the rule, or, rather, perhaps the absence of rule. ...The process is accumulative like a snowball, and returns on itself like a snowball. The obvious affect of frivolous divorce will be frivolous marriage.13

Sources:

G.K. Chesterton Study and Documentation Centre. “Chronology - G.K. Chesterton Study and Documentation Centre,” July 13, 2021. Accessed December 7, 2023. https://cedgkchesterton.cat/en/chronology/.

Milne, Nicholas. “Chesterton’s Ballad of the White Horse: From Conception to Critical Reception.” University of Ottawa. October 15, 2016. Accessed December 7, 2023. https://dc.swosu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1062&context=mythlore.

Chesterton, Gilbert Keith. Eugenics and Other Evils. United Kingdom: Dodd, Mead, 1927. 4.

Chesterton. Eugenics and Other Evils. 13.

From Idiocy to Mental Deficiency: Historical Perspectives on People with Learning Disabilities. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis, 2002. 12.

Chesterton, G. K.. The Autobiography of G.K. Chesterton. United States: Ignatius Press, 2006. 196.

West, Julius. G. K. Chesterton: A Critical Study. United Kingdom: M. Secker, 1915. 175.

Chesterton, Gilbert Keith. The Barbarism of Berlin. United Kingdom: Cassell, 1914. 8.

Chesterton. Barbarism of Berlin. 33.

Chesterton. Barbarism of Berlin. 45.

Chesterton. Barbarism of Berlin. 49.

Chesterton. Barbarism of Berlin. 91.

Chesterton, Gilbert Keith. The Superstition of Divorce. United States: John Lane, 1920. 134.

.png)