Prohibition History and The 18th Amendment

- Brent Hecht

- Nov 3, 2023

- 11 min read

Updated: Nov 5, 2023

A Brief History of Taxes on Alcohol Before 1913

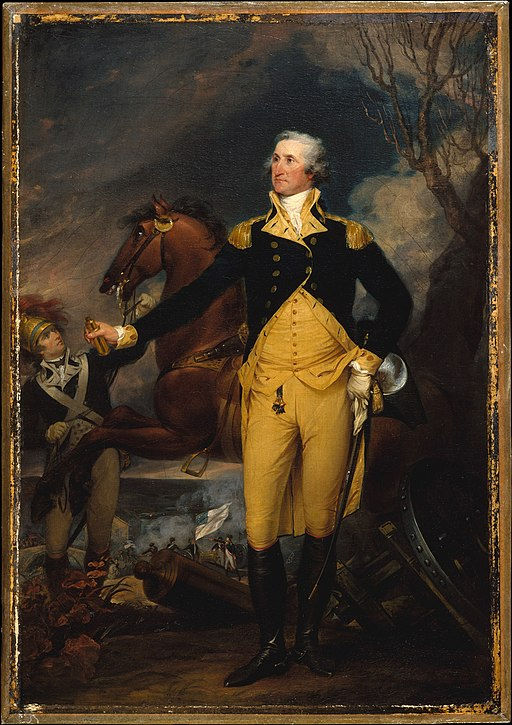

In 1913, nine states in the union had full prohibition and thirty-one others allowed prohibition laws to be enforced at the local level. Views on alcohol consumption were an issue that was central to American politics ever since America's founding. In one example, in March 1776 George Washington exhorted the Continental Soldiers in an address to avoid "tippling houses" where alcohol was consumed. A few months later in September 1776, individual state laws permitted the rationing the quantity of alcohol that a Continental soldier could consume.1 Regulation of alcohol has existed in America since its beginning. Fast forward to today and the Treasury Department regulates the distribution of alcohol and tobacco via the Alcohol and Tobacco Trade Bureau. Here is the TTB's mission statement.

The Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) is responsible for enforcing and administering laws covering the production, use, and distribution of alcohol and tobacco products. TTB also collects excise taxes for firearms and ammunition.2

The Treasury Department's regulation of alcohol has been the tradition since 1791. In 1791, the Treasury Department, under the direction of Alexander Hamilton, began the American tradition of taxing the sale of alcohol by issuing a whiskey excise tax. Hamilton believed the tax would earn $826,000 in annual federal tax revenue which was critical to reducing debt from the revolution.3 When the thirteen states were considering the Constitution, Alexander Hamilton called his shot, describing plans in Federalist Paper 21 that consumption of goods would become a source of tax revenue for the federal government while at the same time limiting consumption of certain products.4 At the time, it may not have dawned on citizens that Hamilton would become the first Treasury Secretary of the United States.

As the 1791 whiskey excise tax was implemented, independence from Britain still remained fresh in the minds of Americans who viewed forced British taxes as one of the primary reasons for the American Revolution. Thus, the whiskey excise tax gave rise to what is known as the Whiskey Rebellion. As the Whiskey Rebellion continued, those who participated were admonished by George Washington in a proclamation issued in September 1792.

. . .tending to obstruct the operation of the laws of the United States for raising a revenue upon spirits distilled within the same...Now therefore I, George Washington, President of the United States. . .earnestly admonish and exhort. . .all persons to refrain and desist. . . 5

Despite George Washington's exhortation, the rebellions continued and in 1794, Washington employed an army to travel to Pennsylvania to put down the rebellions by force. Interestingly, the rebellions in that state were encouraged by the State Legislature in Pennsylvania as they passed resolutions against the tax on June 22, 1792. Pennsylvania legislators believed the tax infringed upon state's rights. The Whiskey Rebellion came to be recognized as the first test of federal authority in the newly formed United States of America.6

To understand the size of the alcohol industry in 1792, there were already 2,579 distilleries in the United States and annual per capita consumption of whiskey was two and a half gallons. There were five million gallons of whiskey distilled every year in the states and another four and half million were imported.7 The whiskey excise tax which started in 1791 remained in effect and varied in amount from year to year until 1802 when Thomas Jefferson abolished the tax completely.

As the Civil War began in 1861, Abraham Lincoln immediately signed a law presented by Congress which prohibited alcohol be sold to Union Soldiers. Also immediately, a federal tax on alcohol once again became law in order to raise taxes for the war. The tax on spirits started at 20 cents per gallon of 100 proof whiskey and when the war ended, it was at 2 dollars per gallon of 100 proof whiskey. The Civil War ended in April 1865 and in that year, the commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service, which was created by Abraham Lincoln in July of 1862, reported that six million barrels of beer are brewed each year and taxes are collected on only two and a half million barrels.8 Many brewers and distillers simply did not adhere to taxation laws. These taxes following the Civil War continued and they varied in amount up until 1913. And as with taxes now, there were stories of politicians succumbing to corruption to tilt the scales in favor of some versus others, such as The Whiskey Ring from 1871 to 1876.9

The first nationwide prohibition amendment proposal was made in the House of Representatives in December 1876 by Henry W. Blair. Then in 1885, Henry W. Blair and Preston Plumb proposed the amendment to the US Senate Committee on Education for consideration. They were Senators from New Hampshire and Kansas, respectively. The Senate Committee referred to the amendment positively and thus placed it on the US Senate calendar in 1886. However, the measure was dropped and not mentioned again.10

Prohibition and the Income Tax

In February 1913, the Sixteenth Amendment was ratified by the states during William Taft's lame duck presidency. The Sixteenth Amendment is the amendment that legalized that an income tax can be issued against the American people. In the following October, Congress and President Wilson passed the Revenue Act of 1913, implementing an income tax. This was integral to the prohibition movement because the income tax provided a new method to generate tax revenue for the federal government. At the time, the tax code worked such that the majority of federal tax revenue came from consumption taxes and tariffs, similar to a sales tax or import tariffs today. In 1913, some claim that 30 to 40 percent of the federal government's tax revenue was generated from alcohol sales.11 Therefore, prohibition was only made possible with the ratification of the Sixteenth Amendment and the implementation of an income tax, which created the capacity to replace taxes on alcohol. . .if prohibition became the law of the land.

Interestingly, prohibition ended in the midst of the Great Depression in 1933. The law had been proven unenforceable by the federal and state government's many shortcomings. In the midst of economic difficulty, the government began collecting taxes from alcohol sales, once again. Americans were now blessed with paying income taxes in addition to the taxes they previously paid on alcohol sales.

Prohibition and Social Issues

Prohibition was also viewed by many to be primarily an important social issue. The Second Great Awakening that occurred in the early 1800s had carried the "temperance movement" forward, which discouraged alcohol consumption in general and especially among Christians. In 1780, John Wesley's Church, the Methodists were encouraged to "disown all persons who engage in distilling."12 In 1810, the Congregational Church and the Presbyterian General Assembly began to team together to promote the temperance movement. Pastors would promote temperance in their sermons and churches created committees to create campaigns to actively sway public opinion. Many of the prominent churches were in agreement that alcohol posed a threat to society.13

Following the Civil War, the temperance movement continued. In 1865 the Presbyterian General Assembly made it illegal for alcohol distillers to become a member of a church in that denomination. Also in 1865, several new temperance organizations were formed including the The National Temperance Society which grew into prominence toward the end of the century.14

Near the end of the century, a new temperance organization burst onto the scene in 1893 called the Anti-Saloon League and had a slogan of "The Saloon Must Go."15 The Anti-Saloon League became the juggernaut organization that guided America to the ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment. The organization created all variety of propaganda by issuing pamphlets, writing songs, creating theatrical dramas, as well as publishing articles in newspapers. Today, the Anti-Saloon League is known as The American Council on Addiction and Alcohol Problems.

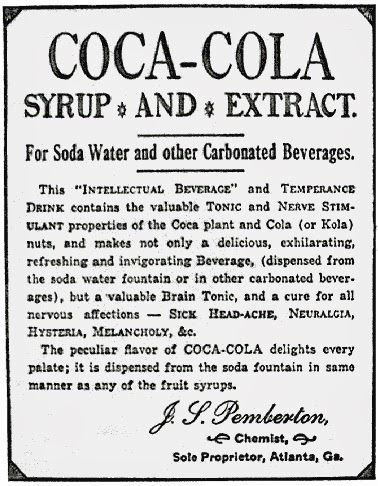

Another interesting story that was born from the temperance movement happened in 1886. During 1860s Coca Wine was invented where people began mixing coca syrup, a form of cocaine, with wine. The temperance movement was not as concerned with cocaine as they were with the alcohol in the wine. Therefore, in the name of temperance, a new drink was created in 1886 by an Atlanta pharmacist, John Stith Pemberton. It was a drink which many called the "temperance drink" and became known as Coca-Cola.16

The Final Push For Prohibition

1906 to 1913

The non-partisan push by the states towards prohibition is believed to have started in 1906 and lasted until 1913. By 1906, the Anti-Saloon League had a strong presence in nearly every state and it was believed that the Eighteenth Amendment was quickly becoming the national consensus among the states. Prior to 1906, it is documented in the Anti-Saloon League's policy documents that they would only push for laws and regulations as far as the public sentiment agreeably allowed.17 By 1906, one-third of the American population was already living under local prohibition laws.

The vote for the Territory of Oklahoma to become a state in 1907 became a watershed event. The issue of prohibition was written into the Oklahoma State Constitution. When the votes were tallied, there was a strong majority that voted in favor or the state's constitution, despite the constitution prohibiting alcohol, thus providing another example of the pro-prohibition sentiment among the people. This further emboldened those such as the Anti-Saloon League that a constitutional amendment may be possible but it wasn't until 1913 that they were fully convinced a national amendment was in line with the public's sentiment.

1913 to 1920

In March 1913, the Webb-Kenyon Act was passed which regulated interstate transport of alcohol. The law was passed in the midst of Taft's lame duck presidency, despite Taft vetoing the bill believing it to be unconstitutional. Congress passed the bill by overriding Taft's veto. The Supreme Court later ruled the bill to be constitutional in 1917 although the Eighteenth Amendment rendered the law obsolete.

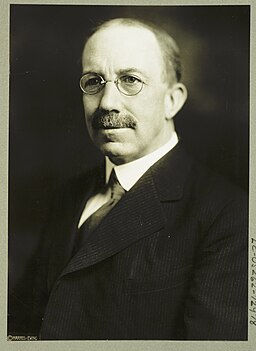

In 1913, the Anti-Saloon League finally believed that it had the required support and sentiment of the American populace to pursue a national amendment. One reason the League was cautious in proposing a constitutional amendment was because although an amendment required two-thirds vote to pass the amendment, the amendment could be changed or altered with only a majority vote. Therefore, the Anti-Saloon League wanted to be very sure they not only had public sentiment in their favor, but also that the members of Congress wouldn't try to water down the bill. In November 1913, at the Fifteenth Annual Convention the Anti-Saloon League officially voted to pursue a national amendment. This meant that not only did the Anti-Saloon League begin to focus on a national amendment, but every other temperance organization in America followed their lead. This 1913 convention also organized a national march which it scheduled for December 10th.18

On December 10, 1913 one of the largest prohibition demonstrations in the history of its movement took place in Washington D.C.. The march proceeded by marching down Pennsylvania Avenue while singing. The march was originally going to be made up of at least 1,000 designated men from the Anti-Saloon League as well as 1,000 designated women from the Women's Christian Temperance Union. However, more than that showed up and so there were over 3,000 men and women in the march. When the march ended, it arrived at the Capitol building where the organizations handed over their proposed resolution for a constitutional amendment to Congress.19

This DC march came just 6 months after the first women's march in DC which, despite its controversy, was considered successful in generating positive publicity for the 19th Amendment.

Opposing Views

Hugh F. Fox, the President of the United States' Brewers Association gave an address in New York City in January 1916 called The Futility of Prohibition. Here are a few excerpts where he argues his case.

Prohibition forces the business of manufacture and sale of liquor from the hands of responsible persons into the hands of irresponsible persons, the baser and lower portion of the population, with the end result that the vilest kind of liquor and liquor substitutes are manufactured and sold illegally.

Even if the federal government could consistently usurp the police power of the States and the communities, I wonder if the problem would not be too staggering for the federal government to grapple with.20

In a report published by W.H. Osborn who was the Commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service stated:

During the past fiscal year, there were unearthed, seized and destroyed, 3832 illicit distilleries, which was an increase of nearly 1,200 over the previous year. . .Nobody has the remotest idea how many were not unearthed.21

The point of this statement is that the enforcement of prohibition was impractical and was ultimately proven impossible.

When the 18th Amendment was ratified, it put out of business 236 distilleries, 1,090 breweries, and 177,790 saloons, all whose business was made illegal.22

The Eighteenth Amendment

Both chambers of Congress passed the Eighteenth Amendment in December 1917, leaving the states to ratify. The first state legislature to ratify the amendment was Mississippi. It was ratified by the 36th out of 48 states, Nebraska, on January 16, 1919.

The 18th Amendment stated:

Section 1—After one year from the ratification of this article the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States and all territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof for beverage purposes is hereby prohibited.

Section 2—The Congress and the several States shall have concurrent power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

Section 3—This article shall be inoperative unless it shall have been ratified as an amendment to the Constitution by the legislatures of the several States, as provided in the Constitution, within seven years from the date of the submission hereof to the States by the Congress.23

The Volstead Act

The 18th Amendment was ratified on January 16, 1919 however, although the amendment had been ratified, it still needed a law that would allow the federal government to enforce it. In January 1920, the Volstead Act, also known as the National Prohibition Act provided the necessary legal backing. When the Volstead Act arrived on Woodrow Wilson's desk on October 27, 1919, he vetoed the bill. He argued that prohibition was only a war-time measure and now that World War I was officially over, there was no more need for the prohibition amendment. The fighting in the war was finished in November 1918, however, the Paris Peace Conference negotiations finally ended in January 1920.24

A day after Wilson vetoed the bill, the veto was overridden by the House and the Senate and passed on October 28, 1919. This allowed the 18th Amendment to begin to be enforced by the federal government on January 17, 1920.

In September of 1920, Wayne B. Wheeler, the leader of the Anti-Saloon League addressed a crowd in Washington DC at the National Conference. One debate surrounding the amendment was the term "concurrent power" found in Section 2 of the amendment. Few contemplated what this meant and it quickly became challenged in the courts. The Supreme Court rightfully decided that the states and federal government have the obligation to cooperate with one another towards the means of effectively enforcing the law. As Wheeler continued his address, he described exactly that, a total cooperation between state and federal governments to enforce the law. He also contemplated what the Anti-Saloon League's role would be in enforcing the law. He stated:

The Anti-Saloon League will have to be on guard many years to prevent the election of a Congress and State Legislatures that will amend or repeal the enforcement codes and thus nullify the Eighteenth Amendment.25

To conclude this article, when you follow the course of American politics surrounding the regulation of alcohol, the topic has been near the center of American politics since the beginning. Since the whiskey excise taxes of 1791 and the Whiskey Rebellion, and then to the enforcing of "concurrent powers" between state and federal government for the regulation of alcohol with the Eighteenth Amendment and the Volstead Act. All of this came to point in January 1920, nearly 144 years following America's founding.

Sources:

Cherrington, Ernest Hurst. The Evolution of Prohibition in the United States of America: A Chronological History of the Liquor Problem and the Temperance Reform in the United States from the Earliest Settlements to the Consummation of National Prohibition, by Ernest H. Cherrington .... United States: American issue Press, 1920. 42.

U.S. Department of The Treasury. “Bureaus,” October 26, 2023. Accessed November 3, 2023. https://home.treasury.gov/about/bureaus.

Cherrington. The Evolution of Prohibition. 54.

“Research Guides: Federalist Papers: Primary Documents in American History: Federalist Nos. 21-30.” Accessed November 3, 2023. https://guides.loc.gov/federalist-papers/text-21-30.

Washington, George., Sparks, Jared. The Writings of George Washington: Being His Correspondence, Addresses, Messages, and Other Papers, Official and Private. United States: American Stationers Company, John B. Russell, 1836. 532.

“Whiskey Rebellion: This Month in Business History (Business Reference Services, Library of Congress).” Accessed November 3, 2023. https://www.loc.gov/rr/business/businesshistory/August/whiskeyrebellion_rev.html.

Cherrington. The Evolution of Prohibition. 54.

Cherrington. The Evolution of Prohibition. 159.

National Archives. “Grant, Babcock, and the Whiskey Ring,” October 21, 2022. Accessed November 3, 2023. https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2000/fall/whiskey-ring-1.

Cherrington. The Evolution of Prohibition. 317.

Fíonta, and Fíonta. “How Taxes Enabled Alcohol Prohibition and Also Led to Its Repeal.” Tax Foundation, July 24, 2023. Accessed November 3, 2023. https://taxfoundation.org/blog/how-taxes-enabled-alcohol-prohibition-and-also-led-its-repeal/.

Cherrington. The Evolution of Prohibition. 68.

Cherrington. The Evolution of Prohibition. 69-71.

Cherrington. The Evolution of Prohibition. 158.

Westerville Public Library. “Anti-Saloon League Collection,” November 3, 2023. https://westervillelibrary.org/antisaloon/.

Wade, Lisa. “How Prohibition Put the Cocaine in Coca-Cola.” Pacific Standard, January 15, 2015. Accessed November 3, 2023. https://psmag.com/economics/how-prohibition-put-the-cocaine-in-coca-cola.

Cherrington. The Evolution of Prohibition. 281.

Cherrington. The Evolution of Prohibition. 319-320.

Cherrington. The Evolution of Prohibition. 322.

Fox, Hugh F.. The Futility of Prohibition. United States: Allied Printing, 1916. 6-8.

Fox. The Futility of Prohibition. 6.

Cherrington. The Evolution of Prohibition. 374.

Constitution Annotated. “Eighteenth Amendment,” n.d. https://constitution.congress.gov/constitution/amendment-18/.

“U.S. Senate: The Senate Overrides the President’s Veto of the Volstead Act,” September 8, 2023. Accessed November 3, 2023. https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/minute/Volstead_Act.htm.

Wheeler, Wayne Bidwell. The Eighteenth Amendment and Its Enforcement: Address. United States: n.p., 1920.

.png)