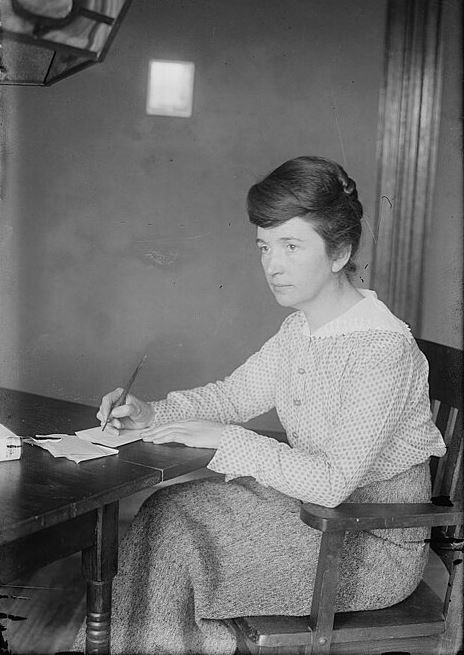

Margaret Sanger and the Feminist Movement

- Brent Hecht

- Sep 2, 2023

- 4 min read

Updated: Jan 18, 2024

Margaret Sanger and the Feminist Movement

In 1913, Margaret Sanger was already political and was drawn to the socialist and feminist movements. As she makes note of in her autobiography, social change was accelerating during this period starting around 1913 and she was eager to deliberately play her part.

Headlong we dived into the most interesting phases of life the United States has ever seen. Radicalism in manners, art, industry, morals, politics was effervescing, and the lid was about to blow off in the Great War. John Spargo, an authority on Karl Marx, had translated Das Kapital into English[1912], thus giving impetus to socialism.1

A religion without a name was spreading over the country. The converts were liberals, Socialists, anarchists, revolutionists of all shades. They were as fixed in their faith in the coming revolution as ever any Primitive Christian in the immediate establishment of the Kingdom of God.2

Sanger's "converted heart" was set on providing contraception/birth-control and trying to find a solution for the lower-class mothers. She described pregnancy as a "chronic condition" in her autobiography and in certain cases, other women shared her sentiment.3 Sanger was by trade, an obstetrical nurse and so she witnessed women's struggles with pregnancy first hand. There was one final case in which she witnessed in July 1912, where a woman tried to perform a self-induced abortion which led to her death. In her autobiography, she credits this as the moment that her obsession with birth-control began.4

With the advice of her husband, the family planned a trip to France to better understand the effects that birth-control had in that country. Unlike the United States, France had liberal laws concerning birth-control and its discussion or use was not illegal at the time. In the United States, discussion surrounding birth-control was prohibited by something known as the Comstock Laws. The Comstock Laws were derived from the Comstock Act of 1873 which made it illegal to publicize, or disseminate information related to unlawful abortion or birth-control. Violating these laws could result in up to five years in prison.5

In October, 1913, the Sangers, her husband Bill and three children, ages nine, five, and three boarded a tiny cabin boat departing from Boston for France. She was in France for only a couple of months and then she decided to return to New York. On December 31, 1913, she boarded a ship in Cherbourg-en-Cotentin, France, leaving her husband behind in France to pursue his career as an artist. Although this was not intended to be a permanent separation, this was the last time her and her husband were together in a close relationship.

Bill was happy in his studio, but I could find no peace. Each day I stayed, each person I met made it worse. ...I could not contain my ideas, I wanted to get on with what I had to do in the world.6

Now back in the United States, in March 1914, she began a monthly publication called The Woman Rebel in which she promoted female contraception using the slogan, “No Gods, No Masters.” This year, 1914, is also the year she coined the term "birth-control."7 The intentions for this publication are summed up by this quote.

Often I had thought of Vashti as the first woman rebel in history. ...because of her disobedience, which might set a very bad example to other wives, she had been cast aside and Ahasuerus had chosen a new bride, the meek and gentle Esther. I wanted each woman to be a rebellious Vashti, not an Esther.8

Sanger's monthly publication, The Woman Rebel, quickly had over 2,000 subscribers.9 Thanks to the Comstock Laws, Sanger was quickly charged with crimes and rather than face her charges, she fled the United States to England. She left her three children behind and her estranged husband William was forced to move back from France to take custody of the children. While in Europe, she continued researching contraception.

In October 1915, she returned and continued to be a "rebel woman" by importing contraceptives she discovered while in the Netherlands that were otherwise illegal in the United States. And just as she was returning home, her youngest daughter Peggy died in November 1915 from pneumonia, sending Sanger into a depressed state.10

In the following year in October 1916, she illegally opened the first birth control clinic in New York City and was arrested 9 days later. After being released she continued opening her clinic until she was evicted by the landlord.

In 1920, she published her first book, Woman and The New Race while also finalizing her divorce from her first husband. Her book, Woman and The New Race opens with these statements:

The most far-reaching social development of modern times is the revolt of woman against sex servitude. The most important force in the remaking of the world is a free motherhood. ...when the world is remade, it will exceed the dream of statesman, reformer, and revolutionist.11

Today, the world is still suffering from the evil ideology of feminism, but men and women alike have awoken to the divisiveness and lies that this ideology propagates.

Sanger, Margaret. The Autobiography of Margaret Sanger. United States: Dover Publications, 2012. 68-69.

Sanger. The Autobiography. 68-69.

Sanger. The Autobiography. 88.

Sanger. The Autobiography. 92.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Comstock Act | Definition, Importance, Effects, & Facts,” Encyclopedia Britannica, August 16, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/event/Comstock-Act.

Sanger. The Autobiography. 105.

American Experience, PBS. “A Timeline of Contraception.” American Experience | PBS, March 13, 2018. Accessed January 18, 2024. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/pill-timeline/#.

Sanger. The Autobiography. 106.

Women's Use of Public Relations for Progressive-era Reform: Rousing the Conscience of a Nation. United States: Edwin Mellen Press, 2007. 107.

“Margaret Higgins Sanger | Encyclopedia.Com,” n.d., https://www.encyclopedia.com/people/medicine/medicine-biographies/margaret-higgins-sanger.

Sanger., Margaret. Woman and the New Race. United States: Truth Publishing Company, 1920. 1.

.png)