Brief History of the Radio from 1886 to 1913

Heinrich Hertz

In 1879, the Berlin Academy of Science offered a prize for research that solved the problem of understanding the "relation between electromagnetic forces and the dielectric polarisation of insulators."1 Heinrich Hertz began studying the problem for a short period of time before losing interest and focusing his attention elsewhere. However, the problem remained with Hertz and in 1886 he had an idea which provided a breakthrough. As a result, in November 1886, Heinrich Hertz became the first to send and receive controlled radio waves, proving their existence.2

Guglielmo Marconi

Following Hertz providing experimental proof of radio waves, many others began to contribute to the work of creating radio communications, including Hertz himself, but no one received as much credit as the Italian inventor, Guglielmo Marconi. In 1892, Guglielmo Marconi turned eighteen and began to be tutored in the sciences by Giotto Bizzarini at the request of his father Alfonso. Bizzarini recorded that "our lessons were conversations on real scientific matters," highlighting the young Marconi's intelligence.3 The same year that Marconi started with Bizzarini, in 1892, Marconi began conducting experiments around the "electrical oscillations produced by atmospheric discharges."4 Just a few years later in 1895, Guglielmo Marconi had created the first wireless telegraph, also known as the radio.5

Guglielmo Marconi started his first company shortly thereafter in 1897 at the age of 24 and called it The Wire-less Telegraph and Signal Company and later it became referred to as British Marconi given it was incorporated in Britain.6 Then, in 1899 he started The Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company of America which eventually became referred to as American Marconi for short. British Marconi reached several milestones in 1899 including wirelessly telegraphing the international yacht race as well as successfully transmitting radio signals between Britain and Europe.7

Other Inventors and Inventions

Over the coming decade, Marconi became a controversial figure. He was able to build a large commercial enterprise by using the British patent system to stifle the innovations of his competition. Even so, it didn't stop several other inventors from innovating. Pioneers in radio technology at the time included names like Reginald Fessenden and Lee De Forest.

Reginald Fessenden in 1906 became the first to conduct a two way transmission across the Atlantic Ocean between Brant Rock, Massachusetts and Scotland. The tower that was erected in Scotland was subsequently destroyed in a storm and the project was never continued. Then in December 1906, Fessenden became the first to transmit voices and music over long distances via radio waves.8 Lee De Forest was able to do something similar in New York City in 1907 with state of the art technology he had created called the Audion Tubes which was a vacuum tube used to amplify radio signals.9 De Forest also started the United Wireless Telegraph Company in late 1906 which grew to become the largest radio telegraph company in the United States until it was acquired by American Marconi in 1912.10

In 1913, Edwin Howard Armstrong, known as the "father of FM radio," invented the regenerative feedback circuit and applied for a US patent which he received in 1914 and licensed his invention to American Marconi. While serving in World War I, he invented the super heterodyne receiver and received a patent for that as well. Eventually Armstrong sold the rights to the heterodyne receiver to the Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company which they used to start the first radio station, KDKA Pittsburgh.11 These patents eventually ended up with the Radio Corporation of America(RCA).

The International Radiotelegraph Convention of 1906

On October 3, 1906, the International Radiotelegraph Convention took place in Berlin. The convention was originally planned for 1904, however circumstances postponed the conference until 1906. The convention's purpose was to arrive at an agreement for international standards concerning radio signal communication. The conference partially accomplished its goal and an agreement was signed on November 3, 1906. Although an agreement was reached, there was some disagreement. Britain and Italy, who were both primary beneficiaries of the Marconi Company, and who invested their capital to build Marconi's network of radio towers, did not sign the part of the agreement that would require radio towers, strategically located around the globe, to be used by any nation that wanted to use them.12

The Titanic and Radio Regulations

The Titanic famously hit an iceberg and sunk on April 14, 1912. The Titanic was supposedly the largest and most technologically advanced ship that had ever been built at the time. And yet, one of the problems when it allegedly struck the iceberg on that evening, were problems with its radio. At that time, it was not possible for the ship to receive more than one radio message at a time as Marconi's radio system would occupy all of the radio waves at once.13 By 1912, there were many amateur radio broadcasters freely broadcasting whatever they wanted to whomever they wanted, clouding the air waves. This prompted the initiative for regulations so that certain radio waves became free from interference. On May 12, 1912 William Alden Smith, a senator from Michigan made a request that regulations be created for radio broadcasters. In light of the Titanic's tragedy, Smith's request was embraced by a Congressional body that was willing and ready to regulate the novel radio industry.14

At the same time, immediately following the sinking of the Titanic, another international radio conference was held in London and an agreement was signed on July 5, 1912. The international agreement was ratified by the United States Senate on January 22, 1913 and the agreement was determined to take affect on July 1, 1913.15 It was resolved that the agreement at London in 1913 would supersede the agreement of 1906 at the Berlin conference. Nearly every nation in the world was in attendance for the London conference and it created a variety of international protocols that primarily regulated interactions between ships and coastal radio stations.16

On December 1, 1912, the Commerce Department created regulations that created what eventually became the National Broadcast Service. The Radio Act of 1912 made it a requirement to hold a license to broadcast over radio waves, which would be granted via the Commerce Department. The licenses determined on which frequencies a person or entity was permitted to broadcast, as well as what hours of the day. No company would be granted a frequency between 200 and 500 kHz as those were the frequencies that transmitted the furthest distance and were the clearest, therefore, those were reserved for the government.17 Additionally, all ships were required to remain constantly on the alert for radio distress signals while at sea. Between the Radio Act of 1912 and the International Agreement at the London Conference, regulation of the radio had begun.

The Marconi Scandal

The Marconi Scandal was a scandal that alleged financial corruption among a handful of high-ranking political figures inside the British government. In 1912, the British government was seeking proposals for building an empire-wide radio network called the Imperial Wireless Chain. At the time, the British empire encompassed twenty-five percent of the world's landmass making this a large and potentially lucrative contract.

The office in charge of the contract was the Postmaster General at the time, Herbert Samuel. Others who were allegedly involved in the scandal included the Attorney General Sir Rufus Isaacs, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George, and the Parliamentary Secretary to the Treasury, Alexander Murray. It just so happened that one of the managing directors of British Marconi was Godfrey Isaacs, the brother of Rufus Isaacs.18

The allegations of financial impropriety began in 1912 and it is unclear who made the first allegations. The Marconi Scandal was covered thoroughly by Cecil Chesterton of the Eye Witness, who was the brother of the well-known GK Chesterton. Furthermore, the French publication Le Matin also covered the scandal and both were sued for libel as a result. In February 1913, Le Matin made explicit allegations that Herbert Samuel purchased shares in the Marconi Company. During the libel trial, it was revealed that the accused didn't buy shares in British Marconi, but rather some of them did in fact buy shares in its subsidiary, the American Marconi Company.19

In a January 22, 1913 record of Parliament, the legal representation for the Conservative Party, Douglas Hogg, stated this regarding the Marconi Scandal:

There is absolutely no precedent in Post Office history for the Imperial Government going into a speculative partnership with a patent-exploiting company and running up the price of patented apparatus against itself. By doing so, it hurts the public in two different ways. Not only is the cost to the public of wireless telegraphy unfairly and unwisely enhanced but the profits of the patent-exploiters are unduly increased.20

Rufus Isaacs provided this statement on October 12, 1912 when accusations became public:

Never from the beginning. . . have I had one single transaction with the shares of that company. I am not only speaking for myself but also speaking on behalf, I know, of both my Right Honourable Friends the Postmaster General and the Chancellor of the Exchequer who, in some way or another, in some of the articles, have been brought into this matter.21

After becoming involved in covering the Marconi Scandal, Cecil eventually served in World War I where he was killed in battle in 1918. In G.K. Chesterton's biography, Ian Kerr writes about the result of the trial of libel against Cecil:

But the summing up was heavily against Cecil, and the jury was out only five minutes before pronouncing a verdict of guilty. The judge then gave Cecil a lecture but only fined him 100 pounds with costs --Although he said 'it is extremely difficult to refrain from sending you to prison.' . . .The verdict was greeted with cheers: in the jubilant words of 'Keith' Jones, 'Against the Marconi Goliath of wealth and power David had more than held his own; he had . . . forced Ministers of the Crown to face public opinion.'22

Some might be wondering if Winston Churchill played a role in the scandal. Winston Churchill was not implicated, however, he and Lloyd George were on a Mediterranean cruise when the allegations began to grow in 1912. Churchill naturally came to the defense of the accused, especially David Lloyd George.23 In the end, the judge simply reprimanded the government officials for their handling of the situation and it was decided that no crime was committed.

American Marconi from 1913 to 1920

In 1912, American Marconi acquired the assets of the financially strained United Wireless Telegraph Company, which was started by Lee DeForest, and became the largest radio communications provider in the United States. Pictured is an example of a 1907 newspaper advertisement from the United Wireless Telegraph Company in the San Francisco Call.24 Advertisements like this one became common from companies like United Wireless as well as the American Marconi Company, promising financial gains to investors. In United Wireless' case, it created many disappointed investors in the end. One of the factors that led to the fall of United Wireless is that the company was allegedly guilty of patent infringement against American Marconi. Therefore, its acquisition by the Marconi Company became primarily the result of a lawsuit which it stood little chance of winning. By October 1, 1912, details of the acquisition became public and investors in United Wireless were fortunate if they were able to recoup ten percent of their investment.25

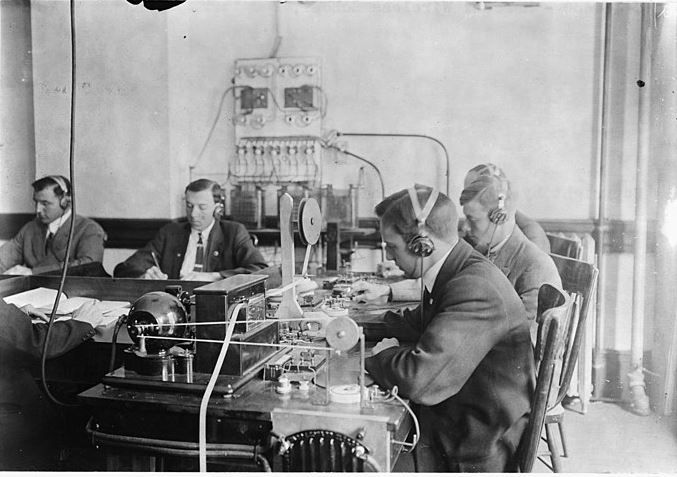

In August 1913, shares of American Marconi were issued to the general public. The shares were issued to provide resources to combine the two companies, as well as to help the company come into compliance with regulations from the Radio Act of 1912.26 American Marconi was headquartered in New Brunswick, New Jersey and in 1913, Edward Nally became the general manager of the company and eventually became the first president of the Radio Corporation of America(RCA) when the company was acquired in 1919.

American Marconi Acquired by General Electric

The General Electric Company was formed in 1892 as the merger between Edison General Electric Company and Thomson-Houston Electric Company. The company was headquartered in Schenectady, New York and grew into a large company by 1913. In 1919, the company acquired the American Marconi Wireless Company with Owen Young as GE's CEO. The acquisition became effective on November 20, 1919 and American Marconi was renamed the Radio Corporation of America(RCA).27

In 1919, General Electric had discovered the Alexanderson Alternator Transmitter which was more effective at transmitting radio signals across the Atlantic. As the Marconi company prepared to adopt these new transmitters across the company, the US Navy recommended that American Marconi be acquired by an American company as a matter of US national defense. This recommendation happened on April 8, 1919 when Captain Stanford C. Hooper and Admiral W. H. G. Bullard met with General Electric executives to request that they not sell their Alexanderson alternators to the Marconi companies. This marked the beginning whereby GE would buy American Marconi and create the Radio Corporation of America(RCA).28

In July 1920, RCA broke ground on what was to become a centralized radio broadcasting terminal on Rocky Point, Long Island. The construction was mostly completed on November 5, 1921, however, technological discoveries in the 1920s made the Alexanderson Alternator Transmitter as well as requirements of a giant radio terminal like the one at Rocky Point, Long Island, obsolete.29

First Presidential Election to Air on Radio

Thanks to the Radio Act of 1912, which went into effect in July 1913, radio licenses for certain frequencies were distributed by the Commerce Department. The Westinghouse company was one of the first to obtain a license. On November 2, 1920, Westinghouse's station in East Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania broadcast under a temporary authorization using an amateur call of 8ZZ, before switching to operating under an official limited commercial license granted by the Commerce Department, as KDKA Pittsburgh. This became the station that, for the first time, broadcast the results of a presidential election in 1920.

Prior to 1920, most Americans couldn’t fathom the idea of voices and music coming into their homes over the air. But the availability of free, over-the-air music and information fueled tremendous growth with sales of in-home radio sets growing from only 5,000 units in 1920 to more than 2.5 million units in 1924.30 This marked the beginning of a new age in media, where print media began to slowly be replaced.

Source:

Hertz, Heinrich. Electric Waves: Being Researches on the Propagation of Electric Action with Finite Velocity Through Space. United States: Dover Publications, 1962. 1.

DES. “KIT - KIT - Media - Press Releases - Archive Press Releases - 125 Years Discovery of Electromagnetic Waves,” August 11, 2011. Accessed January 25, 2024. https://www.kit.edu/kit/english/pi_2011_8434.php#.

History of Technology Volume 32. India: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2014. 263.

History of Technology. 263.

“National Inventors Hall of Fame Inductee Guglielmo Marconi and the Radio,” 2024. Accessed January 25, 2024. https://www.invent.org/inductees/guglielmo-marconi#.

O'Shei, Tim. Marconi and Tesla: Pioneers of Radio Communication. United States: MyReportLinks Books, 2008. 41.

Hanson, John Wesley. Progress of the Nineteenth Century: A Panoramic Review of the Inventions and Discoveries of the Past Hundred Years .... United States: J. L. Nichols, 1900. 242.

“Reginald Aubrey Fessenden | Canadian Scientist & Inventor.” Encyclopedia Britannica, July 20, 1998. Accessed January 25, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Reginald-Aubrey-Fessenden.

“De Forest Singing Arc Type Radiophone Transmitter, 1907 - The Henry Ford.” Accessed January 25, 2024. https://www.thehenryford.org/collections-and-research/digital-collections/artifact/22878/#.

“Of Interest to Wireless Stockholders (1912).” Accessed February 2, 2024. https://earlyradiohistory.us/1912inst.htm.

“Edwin Armstrong | Lemelson.” Accessed January 25, 2024. https://lemelson.mit.edu/resources/edwin-armstrong.

Howeth, Linwood S.. History of Communications Electronics in the United States Navy. United States: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1963. 71-72.

Abelson, Harold., Ledeen, Ken., Lewis, Harry R.. Blown to bits: peril and promise of the digital explosion. United Kingdom: Addison-Wesley, 2008. 264.

Abelson, Harold. Blown to bits. 265.

International Radiotelegraph Convention. United States: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1913. 7.

International Radiotelegraph Convention. United States. 1.

Abelson, Harold. Blown to bits. 265.

“The Marconi Scandal - National Library of Wales.” Accessed February 2, 2024. https://www.library.wales/discover-learn/digital-exhibitions/david-lloyd-george/the-life-and-work-of-david-lloyd-george/the-marconi-scandal.

“The Marconi Scandal - National Library of Wales.”

Parliamentary Papers. United Kingdom: H.M. Stationery Office, 1913. 711.

Spartacus Educational. “The Marconi Scandal.” Accessed February 2, 2024. https://spartacus-educational.com/PRmarconi.htm.

Ker, Ian. G. K. Chesterton: A Biography. United Kingdom: OUP Oxford, 2011. 316.

International Churchill Society. “Spring 1913 (Age 38),” May 11, 2021. Accessed February 2, 2024. https://winstonchurchill.org/the-life-of-churchill/rising-politician/1910-1919/spring-1913-age-38/.

Charles M. Shortridge. “The San Francisco Call. [Volume] (San Francisco [Calif.]) 1895-1913, April 21, 1907, Image 51,” April 21, 1907. Accessed February 2, 2024. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85066387/1907-04-21/ed-1/seq-51/.

“Early Radio Industry Development (1897-1914).” Accessed February 2, 2024. https://earlyradiohistory.us/sec006.htm.

Elizabeth Kruse. “From Free Privilege to Regulation: Wireless Firms and the Competition for Spectrum Rights before World War I.” The Business History Review 76, no. 4 (2002): 659–703. https://doi.org/10.2307/4127706 692.

“The History of the RCA Brand: 100 Years of Technological Innovations.” Accessed February 2, 2024. https://www.rca.com/us_en/our-legacy-266-us-en.

The Sarnoff Collection. “RCA Timeline.” Accessed February 2, 2024. https://davidsarnoff.tcnj.edu/rca/rca-timeline/.

“Rocky Point History – Rocky Point Historical Society.” Accessed February 2, 2024. http://rockypointhistoricalsociety.org/rocky-point-history/.

“Timeline | Celebrating 100 Years | NAB and NAB Show.” Accessed February 2, 2024. https://www.nab.org/100/timeline.asp.

.png)