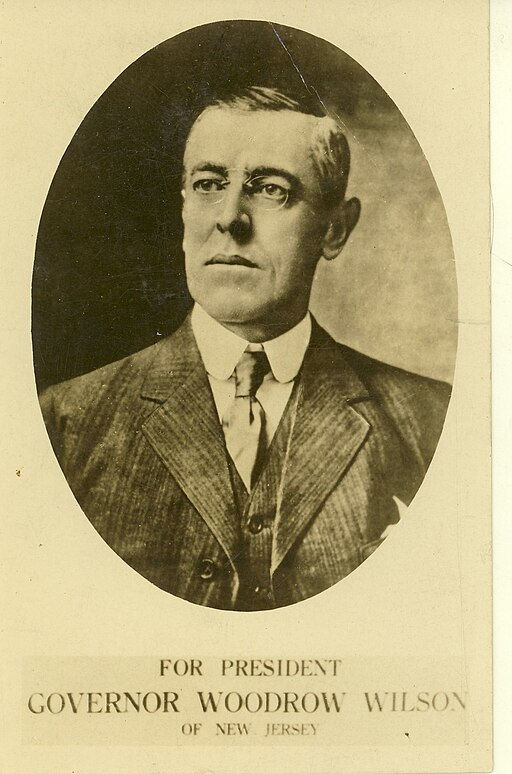

Woodrow Wilson's Campaign Slogan: The New Freedom

When Woodrow Wilson became president in 1913, he compiled his campaign speeches into a collection named after his campaign slogan titled The New Freedom and published them that same year.

As one reads Wilson's campaign speeches, it is clear that Wilson held plans for big changes within government. Not coincidentally, Woodrow Wilson is sometimes referred to as the Father of the Administrative State. It was 1886, when Wilson was already establishing his views on administration within government and the year he authored a thesis paper titled Study of Administration. It is important to read and understand his campaign speeches because it helps provide context for what was happening in 1912 and the challenges that Wilson faced, or at least the ones he believed he was facing. For various reasons, Wilson believed the American government needed to adapt to the changing times, and this became the major theme of his campaign.

As with any presidential campaign during America's history, certain themes reoccur throughout and as one reads Wilson's speeches, it becomes clear that Wilson believed he needed to address the issue of the corporation, trusts, and big business. Wilson lived at a time where several giant corporations had grown up and the wealth that these entities amassed for their primary owners, such as John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, and J. Pierpont Morgan, was a popular political issue in that day. The corporation received the legal status of personhood in 1886 thanks to the Supreme Court Case Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Rail Road which granted equal protection under the 14th Amendment to corporate entities. Interestingly, this was the same year Wilson wrote his paper on the study of administration.

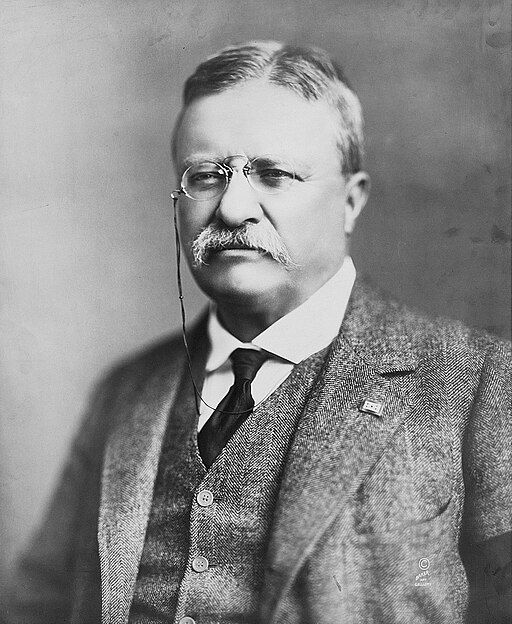

As you read Wilson's campaign speeches, it is important to understand that one of his opponents was Theodore Roosevelt. "Teddy," as some would call him, was running for a third term and was famously known for "trust-busting." Theodore Roosevelt ran as an independent candidate as he had lost the Republican nomination which effectively handed the election to Wilson, the Democrat. Based on Wilson's actions after being elected, one can only conclude that much of his 1912 campaign was disingenuous to some degree. Whether that is true or Wilson was caught up in his idea of advancing what he believed as genuinely beneficial policy for Americans is difficult to determine. That said, with hindsight, many of Wilson's policies were detrimental to America's future. An opinionated view will be shared in the conclusion section of the article.

Chapter 1: The Old Order Changeth

Throughout Wilson's speeches, he continually references the corporation and trusts as the new order of society and grants that they have contributed to the tremendous prosperity America came to experience.

We are in the presence of a new organization of society. Our life has broken away from the past. The life of America is not the life that it was twenty years ago; it is not the life that it was ten years ago. We have changed our economic conditions, absolutely, from top to bottom.1

During Wilson's presidency, World War I shifted the balance of power from the British Empire to the American Empire. Here he acknowledges just how far America had advanced even acknowledging that it seemed like a "new nation." And although it wasn't new, America did in fact, become the most dominant empire in the world by 1920. This period marked the height of the British Empire.

Our development has run so fast and so far along the lines sketched in the earlier day of constitutional definition, has so crossed and interlaced those lines, has piled upon them such novel structures of trust and combination, has elaborated within them a life so manifold, so full of forces which transcend the boundaries of the country itself and fill the eyes of the world, that a new nation seems to have been created which the old formulas do not fit or afford a vital interpretation of.2

Wilson laments the fact that most men had come to work for a corporation at this point in time, whereas it didn't used to be this way in America. When America began, and for the better part of the 19th century, Men[and women] would work as individuals rather than under the umbrella of a corporation.

There is a sense in which in our day the individual has been submerged. In most parts of our country, men work, not for themselves, not as partners in the old way in which they used to work, but generally as employees,--in a higher or lower grade,--of great corporations. There was a time when corporations played a very minor part in our business affairs, but now they play the chief part, and most men are servants of corporations.3

Chapter 2: What Is Progress

This chapter talks about the fact that laws have "not kept up with the change of economic circumstances." Again, Wilson is referring to the changing effect of the corporation and big business. And Wilson believed this forced him to be 'progressive.'

The laws of this country have not kept up with the change of economic circumstances in this country; they have not kept up with the change of political circumstances; and therefore we are not even where we were when we started. . .I am, therefore, forced to be progressive, if for no other reason, because we have not kept up with our changes of conditions. . .Our laws are still meant for business done by individuals; they have not been satisfactorily adjusted to business done by great combinations, and we have got to adjust them.4

Wilson went on to combat those Americans who suggest that it is proper for the United States to do nothing and to let things sort themselves out. Wilson rejected this argument and called it the most "fatuous ignorance" he had ever heard.5 In many cases, this is the progressive argument that government must always step in and regulate.

Wilson went on to make fun of Florida "crackers" in his speech. "Crackers" were characterized broadly as people who were lazy and "never-do-wells."

A friend of mine asked. . .someone to point out a "cracker" to him. The man asked replied, "Well, if you see something off in the woods that looks brown, like a stump, you will know it is either a stump or a cracker; if it moves, it is a stump."6

Wilson, later in his speech pleaded that he was not for change for the sake of change. He only wanted change so far as it was necessary.

Wilson also discussed the nature on which the founding fathers and authors of the Constitution were students of Newton and how they arranged the Constitution according to the natural laws of nature. However, Wilson exclaimed that government does not abide by Newtonian laws, but by Darwinian laws. This goes to highlight the evil of the progressive age which Wilson hoped to usher in. . . an age that forsook the Creator in favor of other, more malleable theories of governance.

The trouble with the theory is that government is not a machine, but a living thing. It falls, not under the theory of the universe but under the theory of organic life. It is accountable to Darwin, not to Newton. . . Living political constitutions must be Darwinian in structure and in practice. Society is a living organism and must obey the laws of life, not of mechanics; it must develop.7

Next, Wilson suggested that the Declaration of Independence is not a useful document unless we can apply it to the circumstances of the moment. He described it not as a philosophical document but more of a "program of action." Continuing on he asks, "What are the items of our new declaration of independence?"8 This once again exemplified Wilson's belief that America was entering a new age where government was fluid and must adapt. Towards the end of his presidency, Wilson became an instrument towards achieving women's suffrage. The 19th Amendment was passed in the Senate on June 4, 1919 after Wilson called a special session in May to convince the Senate to pass the bill. The 19th Amendment was ratified on August 18, 1920.

Chapter 3: Freemen Need No Guardians

Wilson begins this chapter with a commentary of Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton, although lauded for his accomplishments, was responsible for creating the first central banking system within a young American nation. Little did Wilson know that he would be more like Hamilton in his presidency than he could have imagined. Wilson signed the Federal Reserve Act in December 1913, creating the Federal Reserve central banking system America still experiences today.

A great man, but, in my judgment, not a great American. He did not think in terms of American life. Hamilton believed that the only people who could understand government, and therefore the only people who were qualified to conduct it, were the men who had the biggest financial stake in the commercial and industrial enterprises of the country.9

Next, in the following excerpt, Wilson states that he will not create laws that primarily serve business interests. Ironically, Wilson would pass laws during his presidency including "tariff acts, currency acts, and railroad acts," all very abruptly in his first year in office, 1913. Who was helped by these various laws? Was it the small business and individual as Wilson spoke about so frequently in his speeches?

. . .nothing could be a greater departure from original Americanism. . .than the discouraging doctrine that somebody has got to provide prosperity for the rest of us. And yet, that is exactly the doctrine on which the government of the United States has been conducted lately. Who have been consulted when important measures of government, like tariff acts, and currency acts, and railroad acts, were under consideration? . . .The gentlemen whose ideas have been sought are the big manufacturers, the bankers, and the heads of the great railroad combinations.10

Wilson hoped that government could get up out from under the influence of big business. He wanted to sit above business as the governing authority. Although this was Wilson's hope, what happened during Wilson's presidency and since 1920 is more of a partnership with big business more so than a curtailing of special interests.

The government of the United States at present is the foster-child of special interests. It is not allowed to have a will of its own. It is told at every move: "Don't do that; you will interferer with our prosperity." And when we ask "Where is our prosperity lodged?" a certain group of gentlemen say, "With us."11

Here Wilson speaks against the state as a sort of babysitter where government protects the interests of trusts and trustees. And yet, Wilson was responsible for leading the progressive movement and creating the administrative state.

If any part of our people want to be wards, if they want to have guardians put over them, if they want to be taken care of, if they want to be children, patronized by the government, why, I am sorry, because it will sap the manhood of America.12

Chapter 4: Life Comes From The Soil

In this chapter, Wilson once again makes the case that he wishes to deliver power back to common man who is battling on the front lines of society, rather than the wealthy elites. He makes the case throughout the chapter that common people are the soil by which America receives its nourishment and growth.

The chapter starts off like this.

When I look back on the processes of history, when I survey the genesis of America, I see this written over every page: that the nations are renewed from the bottom, not from the top;. . .the real wisdom of human life is compounded out of the experiences of ordinary men.13

So the first and chief need of this nation of ours today is to include in the partnership of government all those great bodies of unnamed men who are going to produce our future leaders and renew the future energies of America.14

Here Wilson refers to his intention to deal with big business and attempt to restore power into the hands of the individual or at least a wider array of individuals.

We have had the wrong jury; we have had the wrong group,--no, I will not say the wrong group, but too small a group,--in control of the policies of the United States.15

In the days of the early 20th century, college was reserved for the upper class citizens to attend. In fact, Wilson was and still is the most educated president in US history, obtaining his PhD from Johns Hopkins University. Wilson infers the privileged status that was required to attend college in this statement. Today, unlike then, the majority of people attend college.

. . .college boys are not in contact with the realities of life, while "common" citizens are in contact with the actual life of day to day; you do not have to explain to them what touches them to the quick.16

Chapter 5: The Parliament of The People

In this chapter, Wilson expresses that America lost the art form of open debate in the public square. He stated that America must return to public debate and not simply debate and make decisions behind closed doors. Perhaps this was a contributing belief that caused Wilson to begin the tradition of delivering the State of the Union Address to Congress in person.

Of course, he was correct that debate should happen in the open, but over 100 years later, the condition of public debate has not improved. Furthermore, although public opinion matters, always allowing public opinion and debate to sway decisions can quickly become the tyranny of the majority and/or the tyranny of the minority. With America becoming what appears to be less homogeneous in its belief in absolute morality derived from its Creator, the weight of public opinion has become a weight that America is forced to laboriously carry, rather than a wind at its back.

For a long time this country of ours has lacked one of the institutions which freemen have always and everywhere held fundamental. For a long time there has been no sufficient opportunity of counsel among the people; no place and method of talk, of exchange of opinion, of parley. Communities have outgrown the folk-moot and the town-meeting. . .Congress has become an institution which does its work in the privacy of committee rooms and not on the floor of the Chamber; . . .It is partly because citizens have foregone the taking of counsel together that the unholy alliances of bosses and Big Business have been able to assume to govern us.17

Wilson expressed an endearing view of the public school system. In this chapter, he expressed that the public school is where many opinions on local government can be shared via school board meetings.

You know the great melting-pot of America, the place where we are all made Americans of, is the public school, where men of every race and of every origin and of every station in life send their children, or ought to send their children, and where, being mixed together, the youngsters are all infused with the American spirit and developed into American men and American women.18

Woodrow Wilson saw the public school as a place for local government, where individuals in the community could get together and discuss issues. Unfortunately, the education system is not where actual government takes place or where actual views and opinions are shared and discussed. Since Wilson's presidency and before, schools have been and continued to become a place of indoctrinating future American citizens, where parent's views of how schools should operate have only a small bearing on the actions of the school board or the way schools are governed at the state level. Today, the actions of public schools are largely dictated at the federal level.

Wilson goes on to state that there is a diverging opinion between those who choose to live in the city and those who live in the country. Thanks to the Seventeenth Amendment, ratified in 1913 during Wilson's presidency, along with other legislation, the opinion of the "city-folk" began to vastly outweigh the opinion of those who chose to live in the country. That's because the ability to choose state Senators was transferred to a popular vote, rather than allowing them to be chosen by the state legislatures. Wilson discusses his intentions for the Seventeenth Amendment again in a later speech.

Further, these statements exhibit a belief in public discourse solely for the sake of public discourse and not for the sake of arriving at the truth of any matter. Public discourse for the purpose of arriving at truth should always be the objective.

The reason that some city men are not more catholic in their ideas is that they do not share the opinion of the country, and that some countrymen are rustic is that they do not know the opinion of the city; they are both hampered by their limitations.19

Here, Wilson defines the importance of democracy in his own eyes and how the American system of government should work. Except the American system was not founded as a democracy, but as a republic. This key differentiation made government in a nation the size of America possible whereas democracy at that scale is very difficult.

The whole purpose of democracy is that we may hold counsel with one another, so as not to depend upon the understanding of one man, but to depend upon the counsel of all. For only as men are brought into counsel, and state their own needs and interests, can the general interests of a great people be compounded into a policy that is suitable to all.20

Chapter 6: Let Their Be Light

In this chapter, Wilson once again declares the need for transparency. Specifically, he calls for transparency regarding politics as well as large corporations and businesses.

Publicity is one of the purifying elements of politics. The best thing that you can do with anything that is crooked is to lift it up where people can see that it is crooked, and then it will either straighten itself out or disappear. Nothing checks all the bad practices of politics like public exposure. You can't be crooked in the light.21

Similar to a portion of chapter 5, Wilson again derides the making of laws behind closed doors by committees.

Legislation, as we nowadays conduct it, is not conducted in the open. It is not threshed out in open debate upon the floors of our assemblies. It is, on the contrary, framed, digested, and concluded in committee rooms. It is in committee rooms that legislation not desired by the interests dies. It is in committee rooms that legislation desired by the interests is framed and brought forth.22

The Payne-Aldrich Tariff Act was an act that was passed in 1909 by President Taft. It raised tariffs on products entering the United States and Senator Aldrich, who it is named after, also became one of the masterminds behind the creation of the Federal Reserve. He was famously documented as the organizer of the suspicious Jekyll Island meeting.23Wilson's disgust with the Payne-Aldrich Tariff was possibly an indicator of Wilson's belief in an income tax which came into affect immediately in 1913 following the Sixteenth Amendment and the Revenue Act of 1913. Wilson discusses tariffs more broadly in the following chapter.

Ever since the passage of the outrageous Payne-Aldrich Tariff Act our people have been discovering the concealed meanings and purposes which lay hidden in it. . .how deeply and deliberately they were deceived and cheated.24

Wilson refers here to a "divine prerogative of a people's will," making reference to the divine prerogative in which British kings ruled for centuries, only here he uses similar language to describe the will of the people.

Wherever any public business is transacted, wherever plans affecting the public are laid, or enterprises touching the public welfare, comfort, or convenience go forward, wherever political programs are formulated, or candidates on, --over that place a voice must speak, with the divine prerogative of a people's will, the words: "Let there be light!"25

Chapter 7: The Tariff - "Protection" or Special Privilege

Wilson begins the chapter by highlighting the "Tariff of Abominations" dating all the way back to 1828, using it as an argument against tariffs. Wilson believed that tariffs could be manipulated by those who would lobby for or against them and that many times, their intentions are shrouded. It was also impossible for any politician to become an expert in tariffs and the knock-on effects that each one would have. Of course, much like today, simplifying the tariff code could have done away with any politician catering to special interests, but when has government come in favor of simplifying the tax code?

As far back as 1828, when they knew nothing about "practical politics" as compared with what we know now, a tariff bill was passed which was called the "Tariff of Abominations," because it had not beginning nor end nor plan. It had no traceable pattern in it. . . .It was an abominable thing to the thoughtful men of that day, because no man guided it, shaped it, or tried to make an equitable system out of it.26

Here, Wilson highlights that there were 'tariff specialists' who would lobby certain committees in Congress and that this would tilt the scales in favor of certain businesses over others.

There has been substituted for the unschooled body of citizens that used to clamor at the doors of the Finance Committee and the Committee of Ways and Means, one of the most interesting and able bodies of expert lobbyists that has ever been developed in the experience of any country. . .with the tariff specialist the average businessman has no possibility of competition.27

. . .the point now is that the protective tariff has been taken advantage of by some men to destroy domestic competition. . .28

Here, when Wilson refers to "great combinations" he means the companies who have merged or combined to become large monopolies, and thus able to control prices. This leads into the next chapters where Wilson discusses the monopoly in greater depth.

There may have been a time when the tariff did not raise prices, but that time is past; the tariff is now taken advantage of by the great combinations in such a way as to give them control of prices.29

Chapter 8: Monopoly, or Opportunity

In this chapter, Wilson discusses the trusts which 'have been put together' and have achieved monopolies.

Big business is no doubt to a large extent necessary and natural. . . But that is a very different matter from the development of trusts. . . . they have been artificially created. . . they have been put together. . .[by] men who were more powerful than their neighbors in the business world, and who wished to make their power more secure against competition.30

Wilson ridicules companies for trying to create monopolies rather than facing each other as competitors.

If I haven't efficiency enough to beat my rivals, then the thing I am inclined to do is to get together with my rivals and say: "Don't let's cut each other's throats; let's combine and determine prices for ourselves.'31

Why, all the rest of the people of the United States are outsiders. They are rapidly making us outsiders with respect even of the things that come from the bosom of the earth.32

Woodrow Wilson acknowledged that monopolies had been created across various industries and even have the ability to collude across industries to protect their interests.

The facts of the situation amount to this: that a comparatively small number of men control the raw materials of this country; that a comparatively small number of men control the water-powers that can be made useful for the economical production of the energy to drive our machinery; that the same number of men largely control the railroads; that by agreements handed around by themselves, they control the prices, and that that same group of men control the larger credits of the country.33

Chapter 9: Benevolence, or Justice?

In this chapter, Wilson names one of his political competitors, Theodore Roosevelt, who was previously known for 'trust-busting' when he was president. Roosevelt ran as an independent candidate in the race but it placed pressure on Wilson to address the major concern that big business and trusts had become.

If there is any meaning in the things I have been urging, it is this; that the incubus that lies upon this country is the present monopolistic organization of our industrial life.34

Wilson accuses Roosevelt of being captured by financial support from US Steel.

I said not long ago that Mr. Roosevelt was promoting a plan for the control of monopoly which was supported by the United States Steel Corporation. Mr. Roosevelt denied that he was being supported by more than one member of that corporation. He was thinking of money. I was thinking of ideas.35

Wilson aimed to create fear and suspicion around the Roosevelt Plan, and that it would create a partnership between government and monopolies.

The Roosevelt Plan is. . . that the government of the United States shall see to it that these gentlemen who have conquered labor shall be kind to labor. . . .And if the government controlled by the monopolies in its turn controls the monopolies, the partnership is finally consummated.36

Wilson stated that his goal was to make monopolies impossible according to the law. Of course, Roosevelt had already proved through his actions that this was also his aim.

Our purpose is the restoration of freedom. We purpose to prevent private monopoly by law, to see to it that the methods by which monopolies have been built up are legally made impossible.37

Chapter 10: The Way to Resume is to Resume

Wilson titles this chapter after the Specie Resumption Act where Horace Greeley, the founder and editor of the New York Tribune, famously stated 'the way to resume is to resume.' During the Civil War, the American monetary system was transformed and had not yet 'resumed' being backed by physical gold and silver, otherwise known as specie. There was fear that returning to a hard money standard would result in collapsing the economy, which was already in the midst of a downturn. Wilson used Greeley's example to urge people not to fear as those then had feared what returning to a hard monetary standard would do. What followed the 'resumption of specie' was the Gilded Age of American economic growth.

Strangely, Wilson began the chapter by praising the American public for tolerating their politicians.

A singular thing about the people of the United States is their almost infinite patience, their willingness to stand quietly by and see things done which they have voted against and do not want done, and yet never lay the hand of disorder upon any arrangement of government.38

Just as today, Wilson acknowledged that representative government had devolved into something different than representative government.

Some persons have said that representative government has proven too indirect and clumsy an instrument. . . Others. . .have pointed out. . .we do not get representative government at all. . .but merely government representative of political managers who serve their own interests and the interests of those with whom they find it profitable to establish partnerships.39

Wilson shared a sentiment that the American public has the wool pulled over their eyes and that the nominations of political candidates is fixed so that regardless of who wins, the special interests become the ultimate winners.

The critical moment in the choosing of officials is that of their nomination more often than that of their election. When two party organizations, nominally opposing each other but actually working in perfect understanding and cooperation, see to it that both tickets have the same kind of men on them, it is Tweedledum and Tweedledee, so far as the people are concerned. We may delude ourselves. . .that we are electing our own officials . . .The fact is we are making an. . . ineffectual choice between two sets of men named by interests which are not ours.40

Wilson refers to alleged examples where Senate seats had been bought and sold. Rather than root out the evil of this alleged crime, Wilson found it as an opportunity to endorse changing a critical structure of the American government as it was founded. This was of course the Seventeenth Amendment and it changed the way that US Senators were chosen. It was ratified on April 8, 1913 and introduced the choosing of US Senators by popular vote rather than by state legislatures.

But you need not be told. . .how seats have been bought in the Senate; . . .Does the direct election of Senators touch anything except the private control of seats in the Senate? We remember another thing: that we have not been without our suspicions concerning some of the legislatures which elect Senators. . .We have had many shameful instances of practices which we can absolutely remove by [allowing] the direct election of Senators by the people themselves.41

Horace Greely's quote was used to end the chapter.

"The way to resume is to resume," said Horace Greeley, once, when the country was frightened at a prospect which turned out to be not in the least frightful; it was at the moment of the resumption of specie payments for Treasury notes. The Treasury simply resumed. . .42

Chapter 11: The Emancipation of Business

In this chapter, Wilson discusses how he intends to free up business opportunities for the common man.

. . .but every impediment to business is going to be removed, every illegitimate kind of control is going to be destroyed. Every man who wants an opportunity and has energy to seize it, is going to be given a chance.43

As I said earlier, there are recurring themes throughout Wilson's speeches and the monopoly and trust were in the forefront of his mind.

What we propose, therefore, in this program of freedom, is a program of general advantage. Almost every monopoly that has resisted dissolution has resisted the real interests of its own stockholders. Monopoly always checks development, weighs down natural prosperity, pulls against natural advance.44

In any event, if the trust doesn't want you to manufacture your invention, you will not be allowed to, unless you have money of your own and are willing to risk it fighting the monopolistic trust with its vast resources.45

Wilson closed the chapter/speech with the hope of freedom. When reading this, one can imagine how it must have inspired hope in his listeners, but alas, it was a false hope.

The strength of America is proportioned only to the health, the energy, the hope, the elasticity, the buoyancy of the American people. The thought of [freedom]. . .shall liberate their energy to its fullest limit, free their aspirations till no bounds confine them. . .46

Chapter 12: A People's Vital Energies

Wilson begin this chapter challenging his audience to imagine what it must have been like to be Christopher Columbus and the vast chain of events that one man's journey across the ocean had inspired.

Never can that moment of unique opportunity fail to excite the emotion of all who consider its strangeness and richness; a thousand fanciful histories of the earth might be contrived without the imagination daring to conceive such a romance as the hiding away of half the globe until the fulness of time had come for a new start in civilization. A mere sea captain's ambition to trace a new trade route. . .47

God send that in the complicated state of modern affairs we may recover the standards and repeat the achievements of that heroic age!48

Wilson believed human freedom needed to be 'adjusted' so that it all came into line. Who would do the adjusting? The US government.

Human freedom consists in perfect adjustments of human interests and human activities and human energies.49

Wilson closed his collection of speeches with this.

Since their day, the meaning of liberty has deepened. But it has not ceased to be a fundamental demand of the human spirit, a fundamental necessity for the life of the soul. And the day is at hand when it shall be realized on this consecrated soil,- A New Freedom,- A Liberty widened and deepened to match the broadened life of man in modern America, restoring to him in very truth the control of his government, throwing wide all gates of lawful enterprise, unfettering his energies, and warming the generous impulses of his heart,--a process of release, emancipation, and inspiration, full of a breath of life as sweet and wholesome as the airs that filled the sails of the caravels of Columbus and gave the promise and boast of magnificent Opportunity in which America dare not fail.50

Conclusion

Woodrow Wilson was a gifted orator and many of Woodrow Wilson's speeches undoubtedly struck a chord with Americans then, just as they likely would today. It is interesting to notice how Wilson's speeches have an eerie resemblance to many modern presidential speeches in the 20th and 21st centuries. Since Wilson's era, I believe the politicians playbook has remained largely unchanged. The playbook is this: promise to fix the problems of the masses by promising to crackdown on big business and special interests while promising benefits to the common man. This always sounds appealing because as politics often does, it pits the majority, against the minority. Then when elected, the President, whoever that may be, caters primarily to the corporate interests, also known as their donors. Since this is where the lion's share of a president's campaign money comes from, the system becomes a self-perpetuating cycle. The government inevitably perpetuates the very thing they promised to exhume. There are bright spots during the 20th century where certain politicians seemed to truly represent the people, but these moments have been the exception, not the rule.

Woodrow Wilson took office in March 1913. In Woodrow Wilson's first year as president, the Sixteenth Amendment was passed which made it possible for a federal income tax on the general populace. In October 1913, Wilson capitalized on the Sixteenth Amendment(ratified during Taft's lame duck presidency) by passing the Revenue Act of 1913, which reduced and removed tariffs from businesses, while implementing an income tax on the citizens of the United States of America. Then in December 1913, he signed the Federal Reserve Act, creating the Federal Reserve. These two pieces of legislation has done more to harm everyday Americans and help big business during the 20th century than many other pieces of legislation combined.

It is no coincidence that when Woodrow Wilson's presidency was over, Warren G. Harding's campaign slogan was A Return to Normalcy. The American people were tired of the dramatic and progressive changes which Wilson and the US Government had imposed upon them, mostly in a time of crisis. During the next twelve years, Republicans dominated American politics, until the Great Depression occurred and Americans once again voted for a new platform. This time, instead of The New Freedom, they got the program of one of Wilson's protégés. That is, they got FDR's The New Deal.

Sources/Citations:

Wilson, Woodrow., Hale, William Bayard. The New Freedom: A Call for the Emancipation of the Generous Energies of a People. United States: Doubleday, Page, 1918. 1.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 5.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 5.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 33-34.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 37.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 37.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 47-48.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 49.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 55.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 57.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 59.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 65.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 79.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 80.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 81.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 85.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 90.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 97.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 102.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 105.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 116.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 125.

Griffin, G. Edward. The creature from Jekyll Island. United States: American Media, 1995. 437.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 126.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 135.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 136.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 139.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 145.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 149.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 165.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 166.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 174.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 189-190.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 205.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 205.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 207.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 222.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 223.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 228.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 230.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 233-234

Wilson. The New Freedom. 253.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 257.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 265.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 269.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 276.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 278.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 280.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 282.

Wilson. The New Freedom. 294.

.png)